Mechanism host-parasite coevolution

During my thesis (06/2007-09/2011) at the University of Basel, Switzerland, under the supervision of Dieter Ebert, I was able to work on the interaction between the crustacean host Daphnia magna and one of its natural parasites, the bacterium Pasteuria ramosa – an important ecological model to study co-evolution. Specifically,

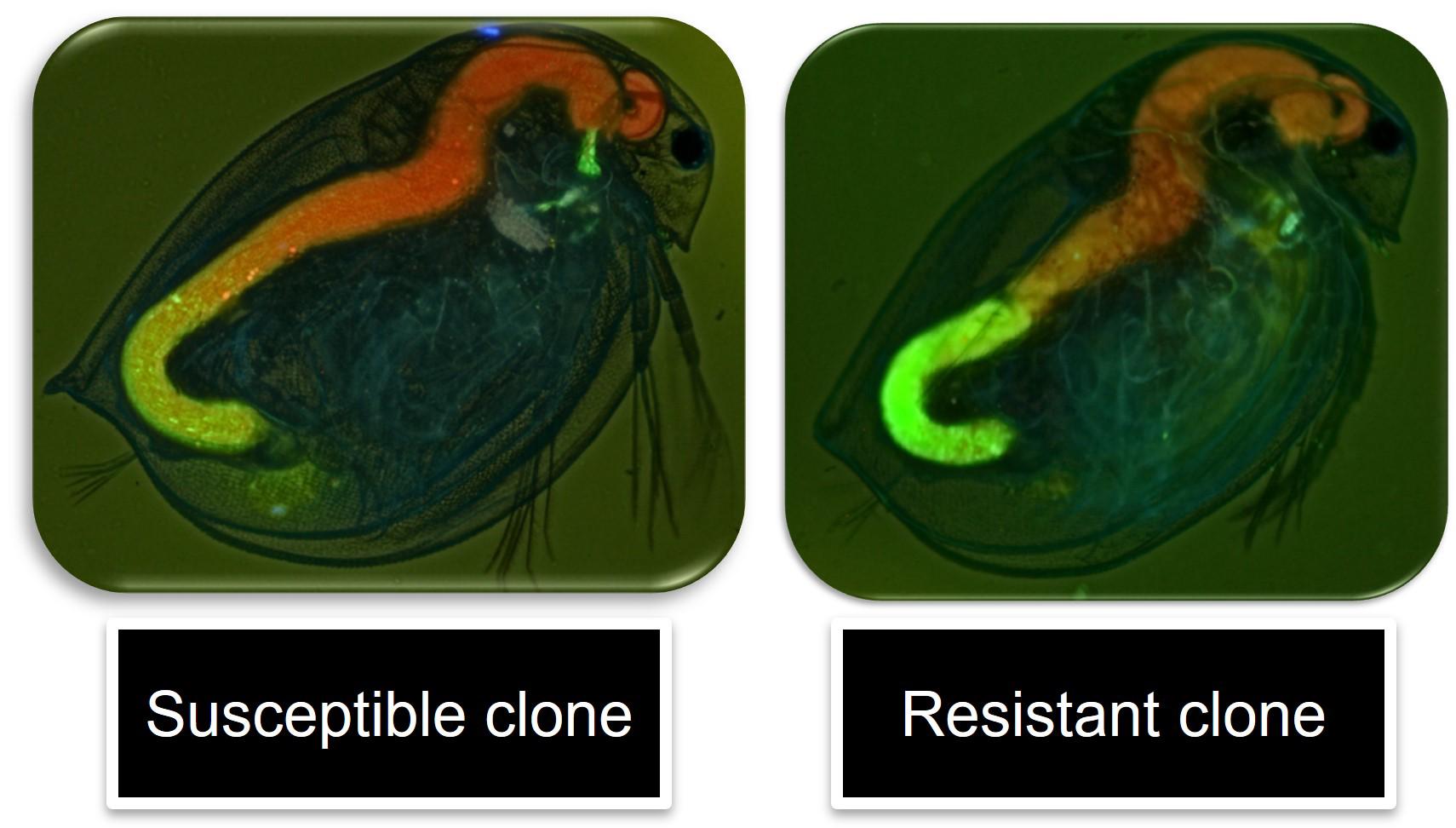

- I developed a method to determine the susceptibility or resistance of a Daphnia genotype to a P. ramosa genotype,

- I described the stages of infection and thus the parameters that affect them,

- which allowed me to discover the stage of infection underlying the cycles of coevolution in this system.

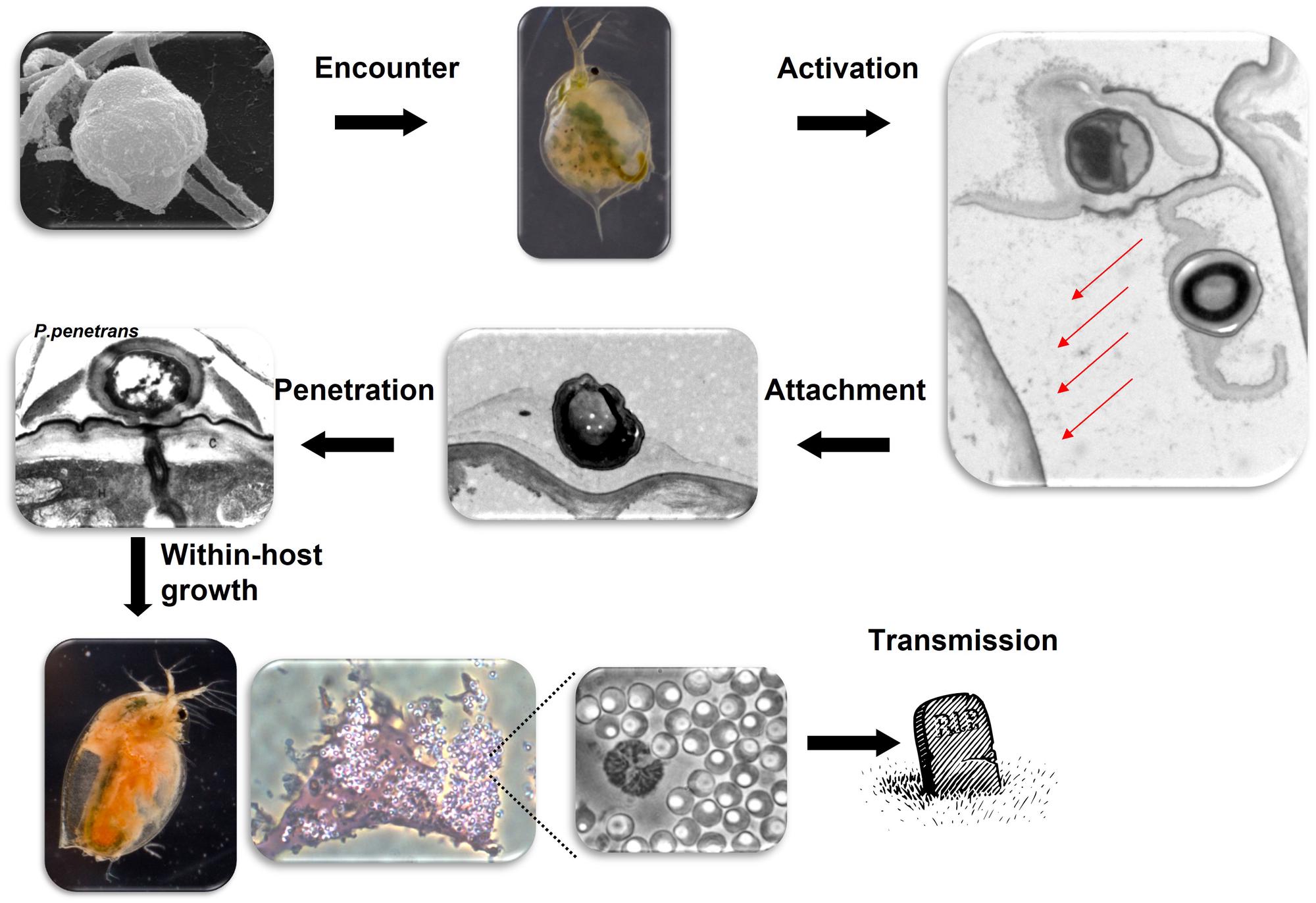

Considering the steps in a relatively simple way, Claude Combes says in his book “Parasitism : The Ecology and Evolution of Intimate Interactions” (1995) that steps in infections can serve as filters that shape host-parasite interactions. In the system of interaction between Daphnia magna and Pasteuria ramosa, previous results suggested that the step at which the parasite must meet its host is crucial and that host behaviour may affect the chances of infection Decaestecker et al., 2002.

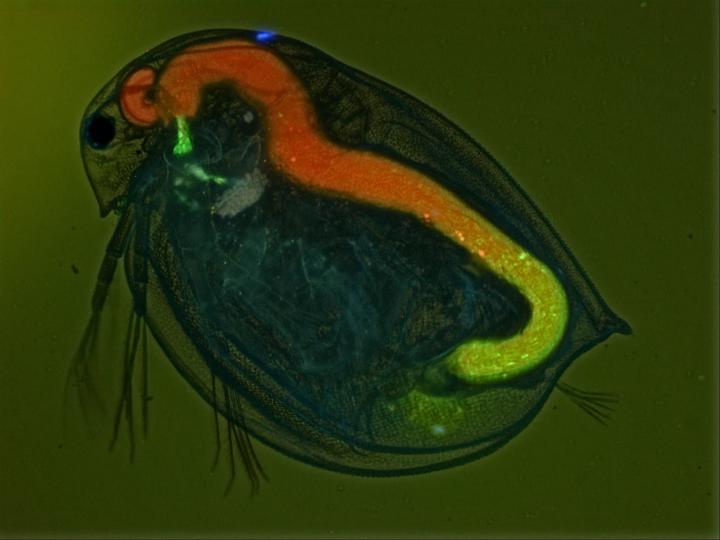

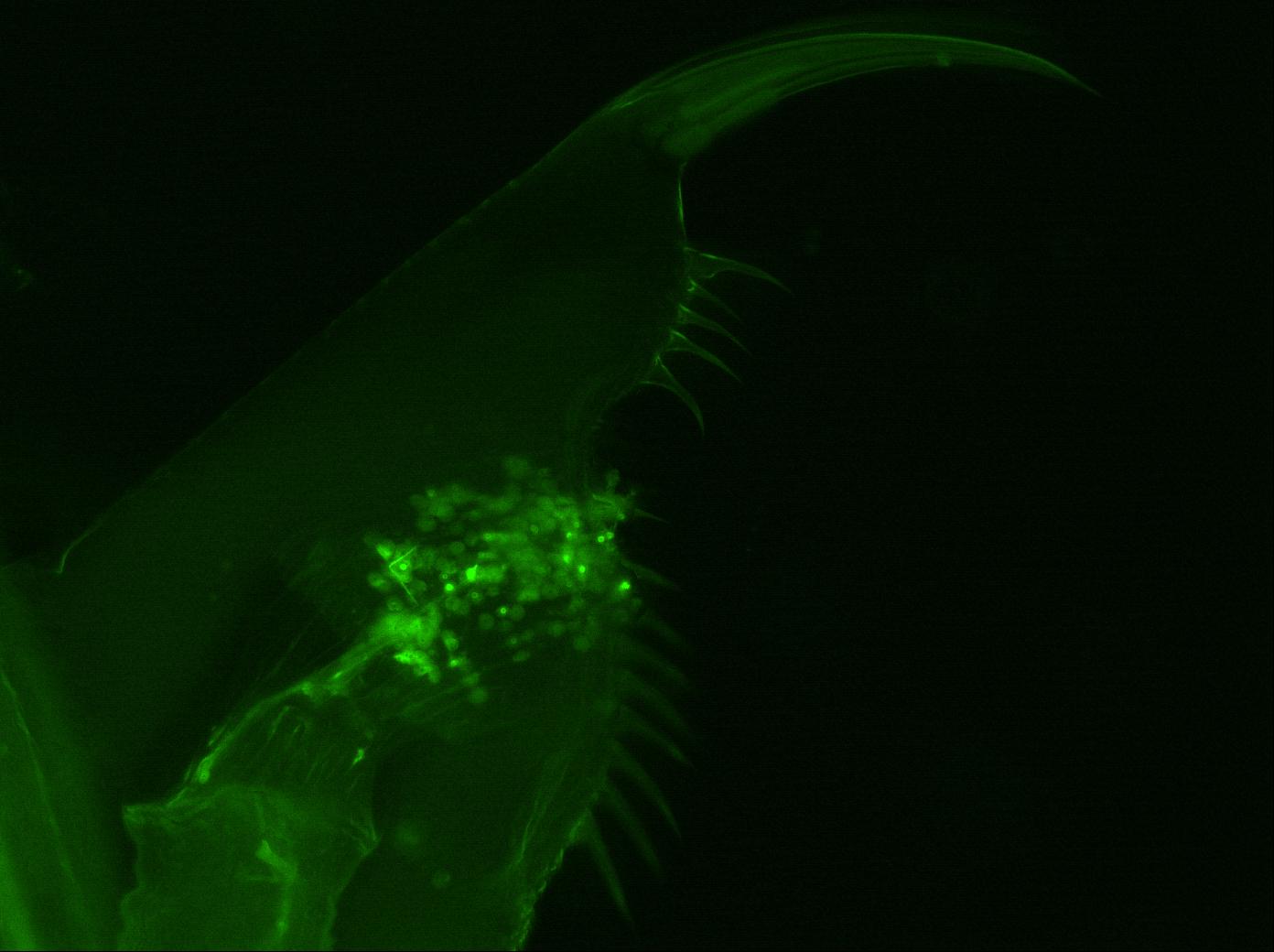

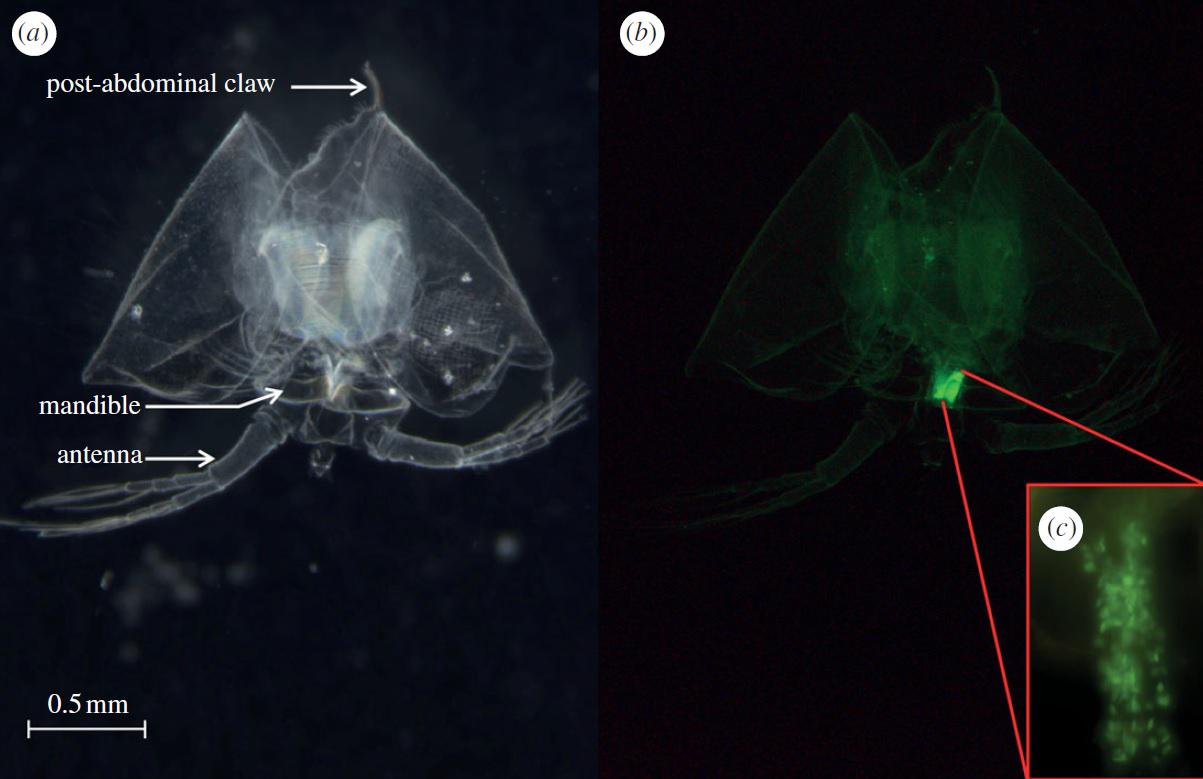

In order to determine the steps that followed this encounter (i.e. activation of the bacterial spore, attachment to the host, proliferation and transmission) and to determine their role in the interaction between the two protagonists, I developed a simple and effective method that is currently used routinely in Dieter Ebert’s laboratory. This method allowed me to first explain that the effect of genotype-genotype interaction on infection success could be completely explained by differences in the probability of attachment of the bacterium to the esophagus of its host, thus revealing the basis of the coevolution between D. magna and P. ramosa Duneau et al., 2011. Neither host density nor sex affected the probability of activation and attachment. Taking into account each individual step made it possible to reconcile theoretical models studying genotype x genotype interaction Luijckx et al., 2012 and Luijckx et al., 2013. Overall, we show that considering the steps of infection was crucial to understand the evolution of host-parasite interactions Ebert et al. 2016.

Some Pasteuria genotypes were able to infect the host without attaching to the oesophagous. Before the end of my PhD, I found that those genotypes were able to go through the gut and attach to the hindgut before being released. In collaboration with Gilberto Bento and Peter Field, we showed that this alternative strategy had a different genetic basis and opened a whole area of research Bento et al. 2020.

Using this method and reasoning, we showed that the different resistance alleles in the host had diverged for several million years, making it the oldest polymorphism described in animals to our knowledge. We also established that bacteria evolving in a population of Daphnia magna could attach to the esophagus of Daphnia pulex, a host in which they had not evolved, but were only able to proliferate in Daphnia magna. We have thus demonstrated that specialization for the host species is specifically at the level of the proliferation stage Luijckx et al., 2014.

We then showed that the cuticle that covers the esophagus on which the bacteria attach carries with it, at the time of molting, the bacteria that had not yet penetrated the host. In fact, we have shown experimentally that individuals who molt within 12 hours after attachment of the bacterium can avoid being infected. Thus, we have shown for the first time that molting, a process generally considered a phase of weakness, can also prevent infections. However, this mechanism seems too constrained by development to be induced Duneau and Ebert, Proc. B, 2012. This work has aroused the interest of the media (e.g. Le Figaro & Live Science) .

Finally, we challenged the idea that Daphnia magna has a specific immune memory to reduce the risk of intra-host proliferation. To achieve this result, we had to carry out a large number of controls, use antibiotics to ensure that the bacteria from the first infectious challenge was no longer in the host, and wait more than a week before reinfecting the host, in order to increase the likelihood that the immune response related to the first challenge has disappeared. By quantifying intra-host proliferation and the probability of infection when hosts were previously exposed or not to a P. ramosa genotype, we found no evidence to validate the hypothesis that there is immune memory in this invertebrate model Duneau et al., 2016.