Sexual dimorphism of diseases

The most striking differences among individuals in a population are often those between the sexes. Such dimorphism is often characterized by obvious differences in morphology and behavior, as well as in a number of differences in physiological functions, including immunity, metabolism, and disease outcome. The sex of the host influences both the dynamics of infections and host symptoms. The sexual dimorphism regarding the response to infection is generally seen as a by-product of the sex-specific roles in reproduction (e.g. males in mammals have a lower immune efficiency because of the physicial interaction between antibodies and testosterone). I am working on the hypothesis that the sexual dimorphism is partly due to the adaptation of the hosts and of the parasites in response to sex-specific exposure to infections.

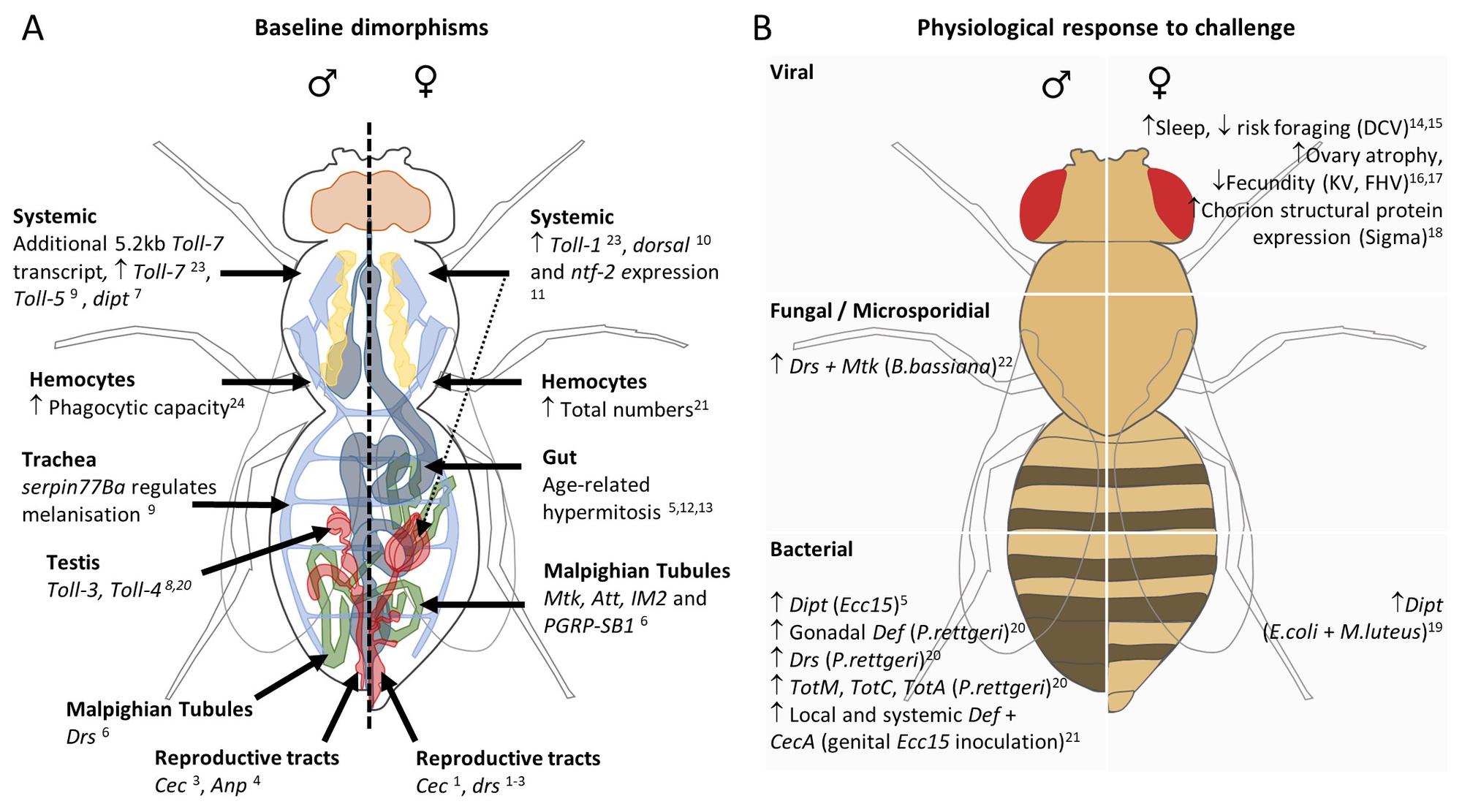

In collaboration with the lab of Jennifer Regan, we have recently reviewed that Drosophila are almost always dimorphic when it comes to respond to an infection (Belmonte et al., 2020).

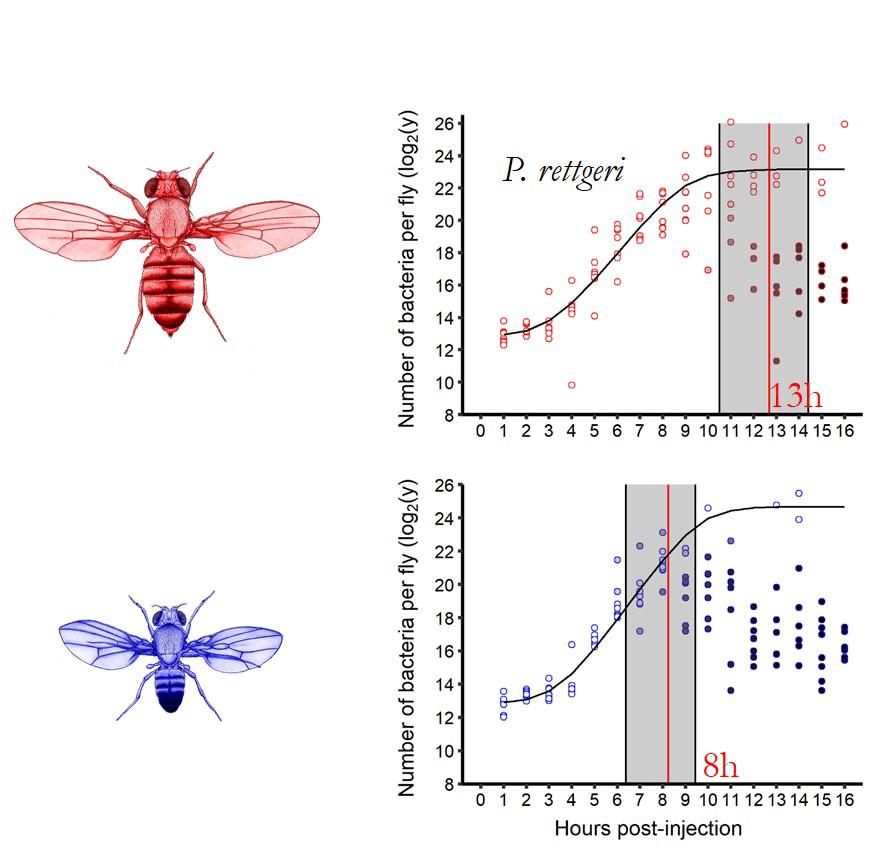

During my time in Cornell, in the Laboratory of Brian Lazzaro, we have shown that part of the reason for this dimorphism is due to a difference in resistance. Using statistical methods, we were able to compare the dynamic intra-host between sexes and we have shown that males control the bacterial proliferation on average few hours earlier than females which makes for the whole difference in survival (Duneau et al., 2017).

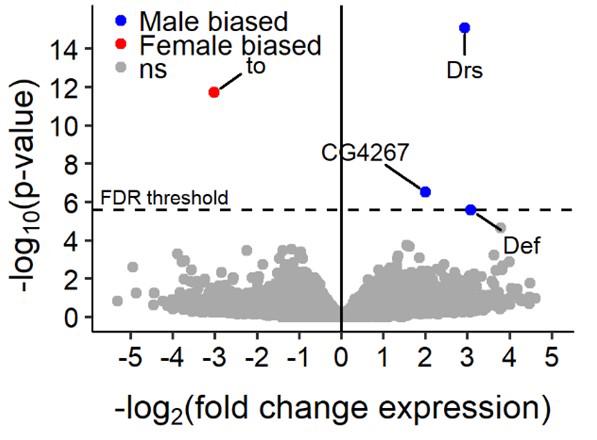

Using whole genome transcriptomics and functional genetic tools, that allow us to modify host characteristics, we showed that this difference in resistance was due to a difference in innate immunity.

More particularly, males and females differ in their recognition of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial infection by the Toll pathway via the Persephone branch of the immune system. Hence, our results suggest not only that studies on immunity should include both sexes, a practice that concern so far only 14% of the studies with (Drosophila) (Belmonte et al., 2020), but also that both sexes represents different environments to their parasites, an observation that is likely to play a role on parasite evolution.

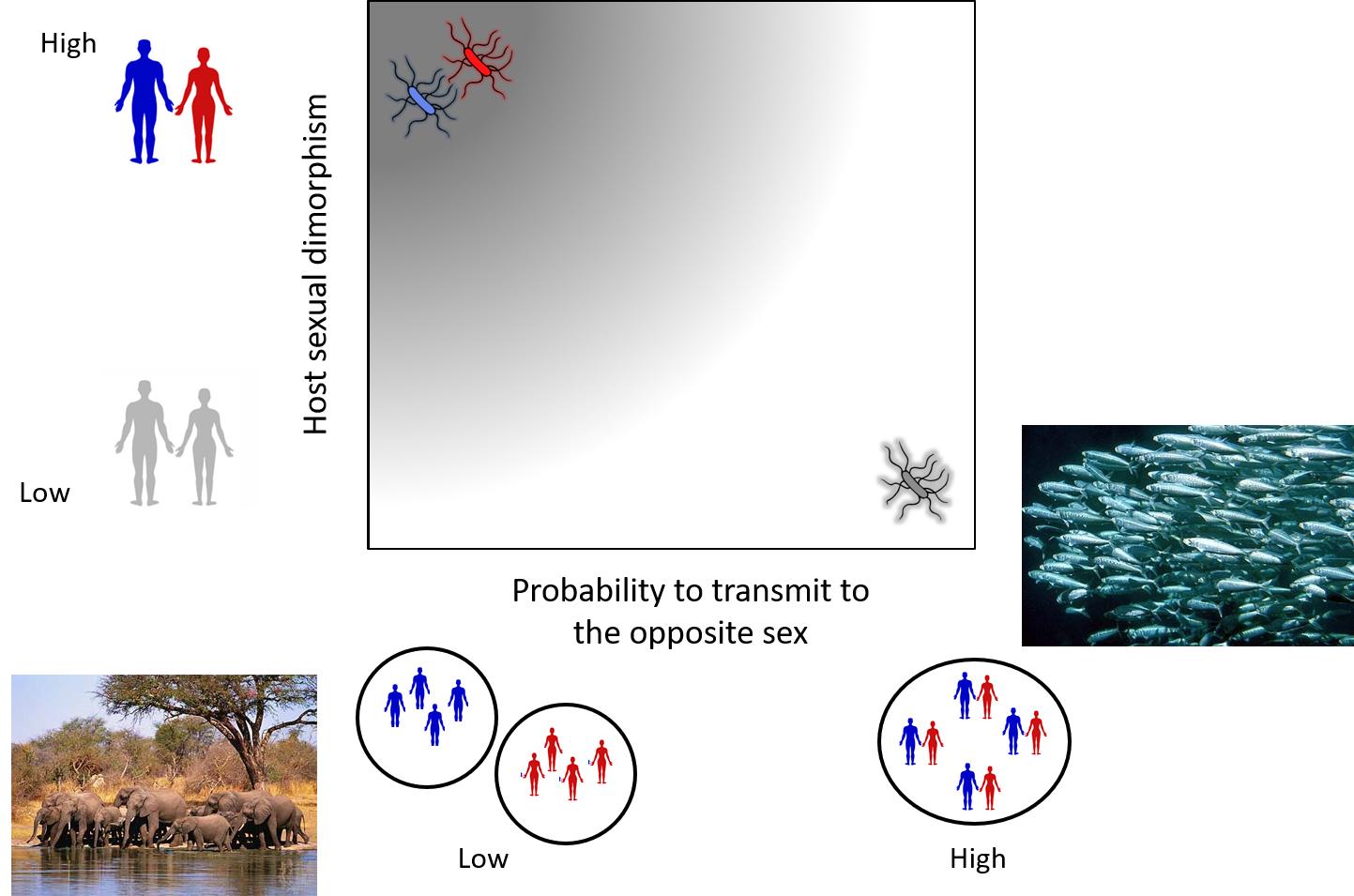

I have been interested in parasite sex-specific evolution since when I was working with Daphnia, a small crustacean living in ponds throughout the world. Research on the Daphnia model has almost always been done in females. This is due to the fact that in most natural conditions the populations are overwhelmingly female. Such extreme bias in sex-ratio, provided the perfect setting to test whether parasites in those populations were better adapted to the characteristics of the sex they encountered the most frequenty. Together with my PhD supervisor Dieter Ebert, we first proposed that a parasite is all the more likely to adapt to one sex that, on the one hand, it proliferates more often in one sex than in the other and, on the other hand, the differences between the sexes are important (Duneau and Ebert, 2012). In this article, I list a number of conditions under which parasites can be expected to adapt to one sex of their host. I argue on the basis of examples that the sex differences in symptoms and prevalence described for many parasites are partly explained by the properties of the parasite and not only, as is commonly claimed, by those of the host.

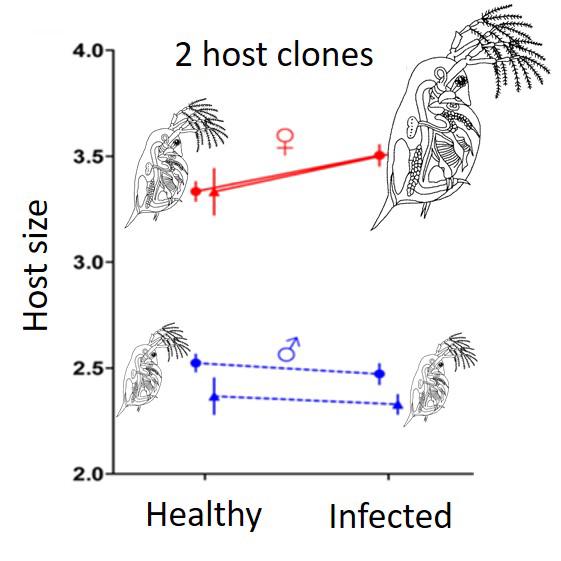

We then tested my hypothesis with Daphnia magna and its parasitic bacterium Pasteuria ramosa Duneau et al., 2012. This pathogen evolves in host populations that are predominantly female and we were able to show that, as expected, it exploited females better than males. The parasite was known to induce castration of its host (female) as an adaptation to induce gigantism and increase the carrying capacity of its environment. We confirmed that the parasite induced an increase in carrying capacity through gigantism in females. However, if the males were also castrated by the infection, this had no effect on their size. In fact, the adaptation that is advantageous when the females are infected (the common host) is not advantageous when the males are infected. We therefore revealed a sex-specific adaptation of a parasite in nature.