Within-host dynamics and disease outcomes

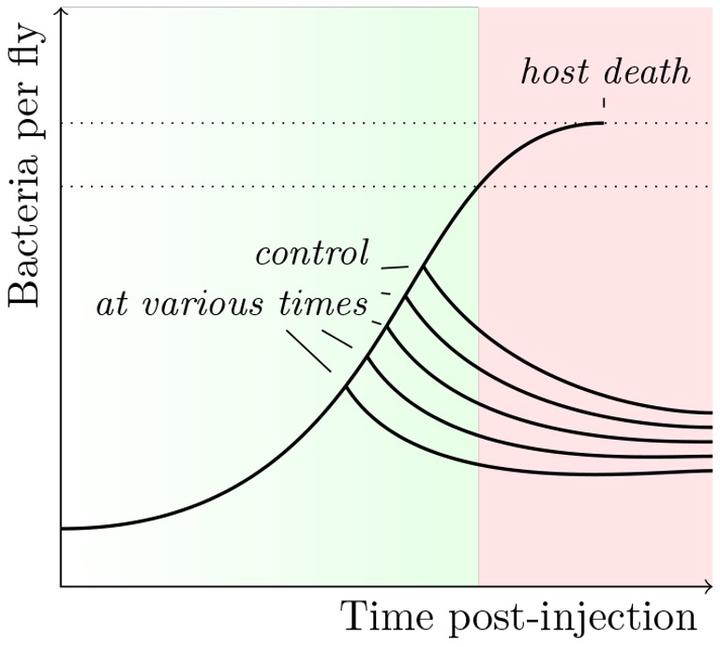

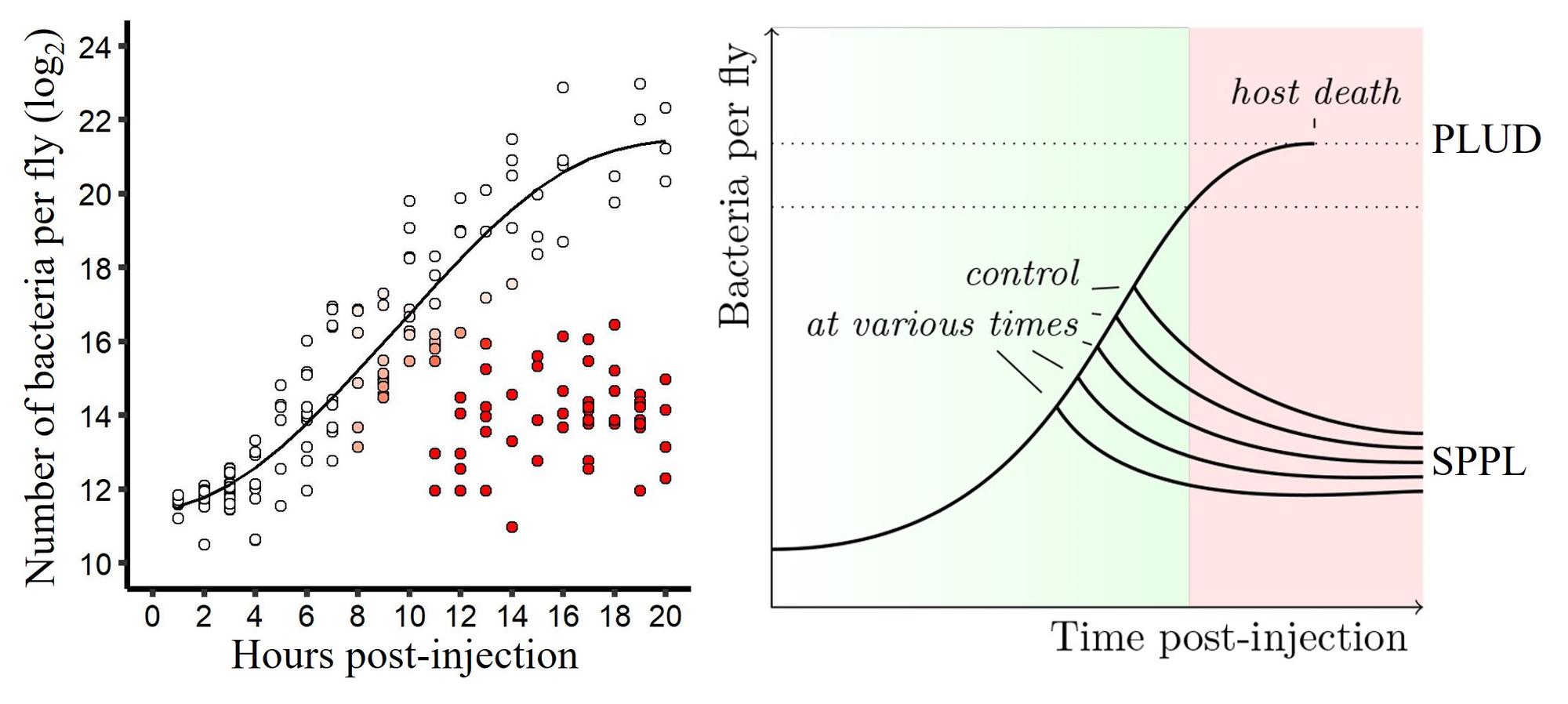

This part of my post-doc can be seen as an extension of my “step-by-step” approach to infection, which was the heart of my thesis. I took advantage of the tools offered by D. melanogaster to study in detail the step were pathogens proliferate within their host. I studied the impact of the variations during this step on the outcome of the infection Duneau et al. 2017. Within a population of sick hosts, individuals are not equal when facing diseases. This variation, which sometimes results in the survival or death of hosts, is present even when controlling for the host’s genetics and environment. We studied the role of the step of proliferation in mortality variation. Thanks to a monitoring over time of bacterial populations within the hosts of the same population and using modeling tools (“mixture models”), we were first able to describe the phases of the proliferation and propose measures to characterize it.

- Time to control the infection (Tc)

- Pathogen Load Upon Death (PLUD)

- Set-Point Pathogen Load (SPPL)

By modifying the immune characteristics of the host, we were able to determine the relative roles of the host and the parasite in these phases and we established that the variation in the probability of survival depends on the variation in a key parameter of the infectious process: the time that the hosts take to control bacterial proliferation. A difference of a few hours in this control time can make the difference between survival and death.

The tipping point is here described as a simple function of the load but it is most probably not as simple and it might depend on the time at a given load too. In other words, a host may reach this tipping point by not being able to tolerate damage received over a certain period of time by a given, and eventually stable, bacterial population that it was initially able to tolerate.

In collaboration with Jean-Baptiste Ferdy, we have used theoretical model and experimental approach to define more specifically the parameters of the infections and determine their role in the two strategies to survive an infection (i.e. controlling the infection - resistance- versus the tolerance of the damage linked to the infection - disease tolerance) Lafont et al. bioRxiv 2021. This work aims to finely describe the dynamics of bacteria interacting with the hosts, understand appropriately the parameters, and to compare dynamics statistically.

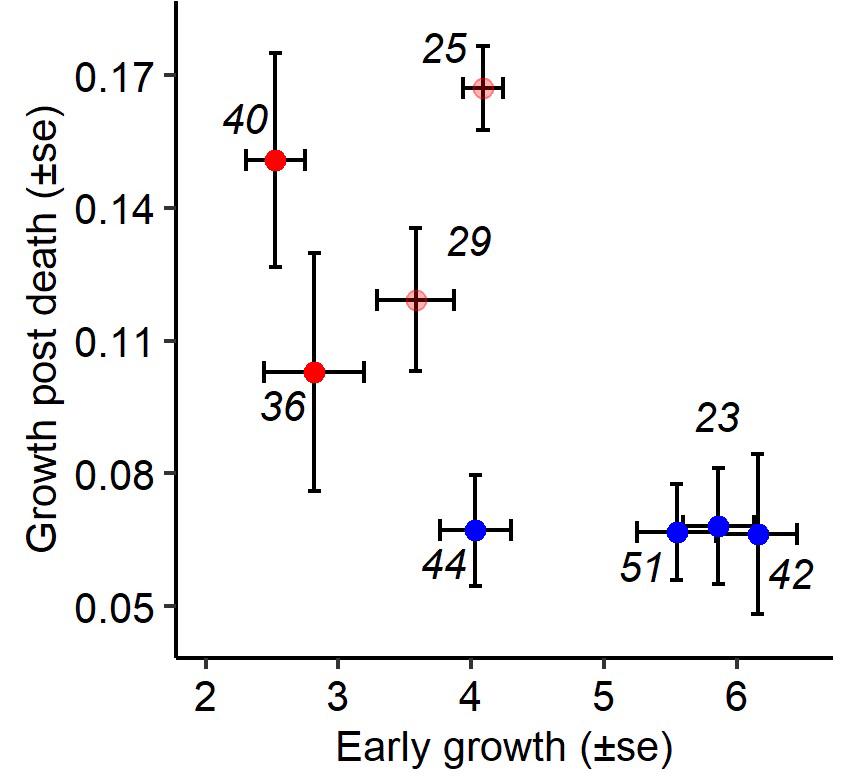

A continuation of this work allowed us to show that our approach could also be used to characterize the impact of mutations in bacterial pathogens on infection outcomes Faucher et al., 2021. The bacterium Xenorhabdus nematophila is in symbiosis with a nematode (Steinernema carpocapsae) to kill insect hosts. The bacterium, carried by the nematode, kills the host and waits until the nematode has reproduced in the host’s corpse to reassociate with its vector. During the course of an infection, selection alternately favours two morphs, one that allows the success of the infection and one advantaged in the corpse. The mutation responsible for this second morph has been identified as a mutation in the Lrp gene, a mutation that generally gives an advantage in the stationary phase of growth (mutation called GASP). Our study uses Drosophila’s genetic tools and the statistical method we developed to characterize the impact of different types of Lrp mutations on infections and understand the characteristics that selected them. We show that GASP mutants are all less virulent but that only missense mutations make bacteria more sensitive to the immune system during proliferation at the beginning of infection. The number of bacteria at the time of death (PLUD) is not affected, suggesting that the toxicity of the bacteria is not altered by the mutation, and that only differences in the ability to grow in the host are responsible for differences in virulence. We show, on the other hand, that the better post-mortem growth of mutants correlates negatively with their virulence, suggesting a trade-off between both traits.

This study introduces a new approach to studying the effects of bacterial mutations in infection, an approach that will be crucial in my future research to characterize experimentally bacterial pathogens.